I recently discovered something in my family history, after spitting in a test-tube for ancestry.com. This little piece of history belongs to my Dad’s maternal line. It got me thinking: why do we often lose our female family members’ stories?

Discovering my family history

When I moved to Wellington 10.5 years ago, my entire family was based in Northland and Auckland. The family history I knew about was my father’s paternal line and my mother’s paternal line. Some of the Irish side of the whānau came to New Zealand in 1848, as part of the fencibles (retired soldiers who had to ‘defend’ NZ against Māori attack), heading straight to Auckland.

In moving to Wellington, I was setting out to live on soil my ancestors had never trod on – or so I believed. When I drove my VW and all my belongings here in the winter of 2013, trekking down from Auckland, I did so because I had a strange connection with the hills of Wellington, its colourful wooden houses, and the friendly, walkable city. I had also just moved back to NZ from London and was itching to live somewhere new. Over the years that I’ve lived here, I’ve lamented the fact that I don’t have family here, and more specifically, my whakapapa/ ancestors are not from Wellington.

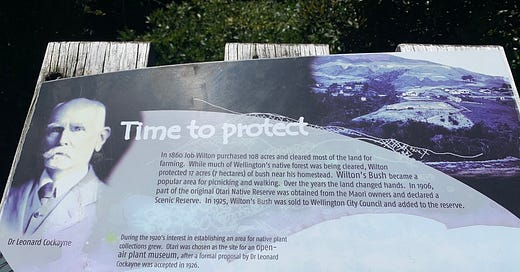

A couple of months ago, I decided to do an ancestry.com DNA test as a Christmas present to myself. While waiting for the results, one evening, I was inputting names into my family tree on ancestry.com (something they encourage you to do as an add-on to the DNA test). The website suggested that my great-grandmother’s last name was Wilton. A few things clicked in my mind. There’s a suburb in Wellington called Wilton, and Otari-Wilton’s bush is a native bush reserve I’ve been to several times. I visited it again and took a photo of a sign there, which mentioned how the reserve had came to be, wondering if there was a connection between the Job Wilton mentioned and my great-grandmother.

Googling a few things, and using ancestry.com’s pre-population feature, revealed that Job was indeed related to me. His brother Henry was my great-great grandfather. The Wiltons were one of the first Pakeha families to settle in Wellington, arriving from Somerset, England, on the Oriental in 1841. Job Wilton bought some of the land where Otari-Wilton’s bush now stands from another Pakeha, in 1860. He fenced 17 acres of it as a reserve, to preserve the original bush. It was officially gazetted in 1906 as a scenic reserve. Now, it’s a native botanical garden with plants and trees that are studied for research, and a site for tourists and locals to see what New Zealand looked like before so much of our environment was converted to farms and houses. There’s more on the history of the land pre-colonisation, and the hapu that lived there, here. Some of the family, including Henry, moved to Masterton and went farming there. My great-grandmother May was born in Masterton - the last of eleven children.

So all along, my ancestors were looking over my shoulder! And yet, I’d never heard about any of this from my grandmother or father (both of who died several years ago, so I can’t ask them about it now.) Much of what I previously knew about my family is centred around the paternal lines, and their occupations. Are male family names so prominent in our psyche that we lean towards researching them, collecting up tidbits of information, photos and stories, instead of learning more about the women’s stories?

How do the maternal lines get lost?

I did some digging into how women’s stories become lost. The lack of documentation and information available could be the result of legislation and social standards of the time. Because women lacked the same rights as men, they were often left off official records. One of my friends, also with a family arriving in 1840 to Wellington, said that she tried to find information on the wife of a male ancestor of hers. The ship records simply say “wife of x”. Not even a first name!

The Married Women’s Property Act (1870; extended in 1882), in England, Ireland and Wales allowed women to inherit property in their own right and to take court action on their behalf (Traceyourpast.com) Prior to this act, if a woman had a will, often wording would state that any of their property/money was to be free from the control of their husband – otherwise any earnings/property/money would be legally owned by their husband. With such a view on women’s property, it’s no wonder not many women’s names were recorded. They weren’t deemed that important.

In my case, the surname of my great-grandmother was almost lost to history as I had never seen it documented on paper or been told her maiden name.

Wealth can also affect what is available. The wealthier the family, the more likely that records would’ve been kept by their local parish, for example. This is something I’ve witnessed, as there seems to be a lot of information on those in my family with land and property (even tenant farmers), but it is trickier to find information on those who were poorer – for example labourers, or those who moved around frequently to find work.

Genealogy websites suggest that in order to trace female ancestors, researchers should look at electoral registers, occupational registers (such as nursing and teaching, which were (are) predominantly female), and even read local history books to place themselves in women’s footsteps – to get a sense of their daily lives.

I feel grateful to know that I’m more connected to Wellington than I once considered myself. As homage to your female ancestors, is there anything you want to know about them, or the times they lived in? Do you have interesting stories about them, that have passed down through your family? I’d love to know…